Image E72tQ7wX0AAxQg1jpg

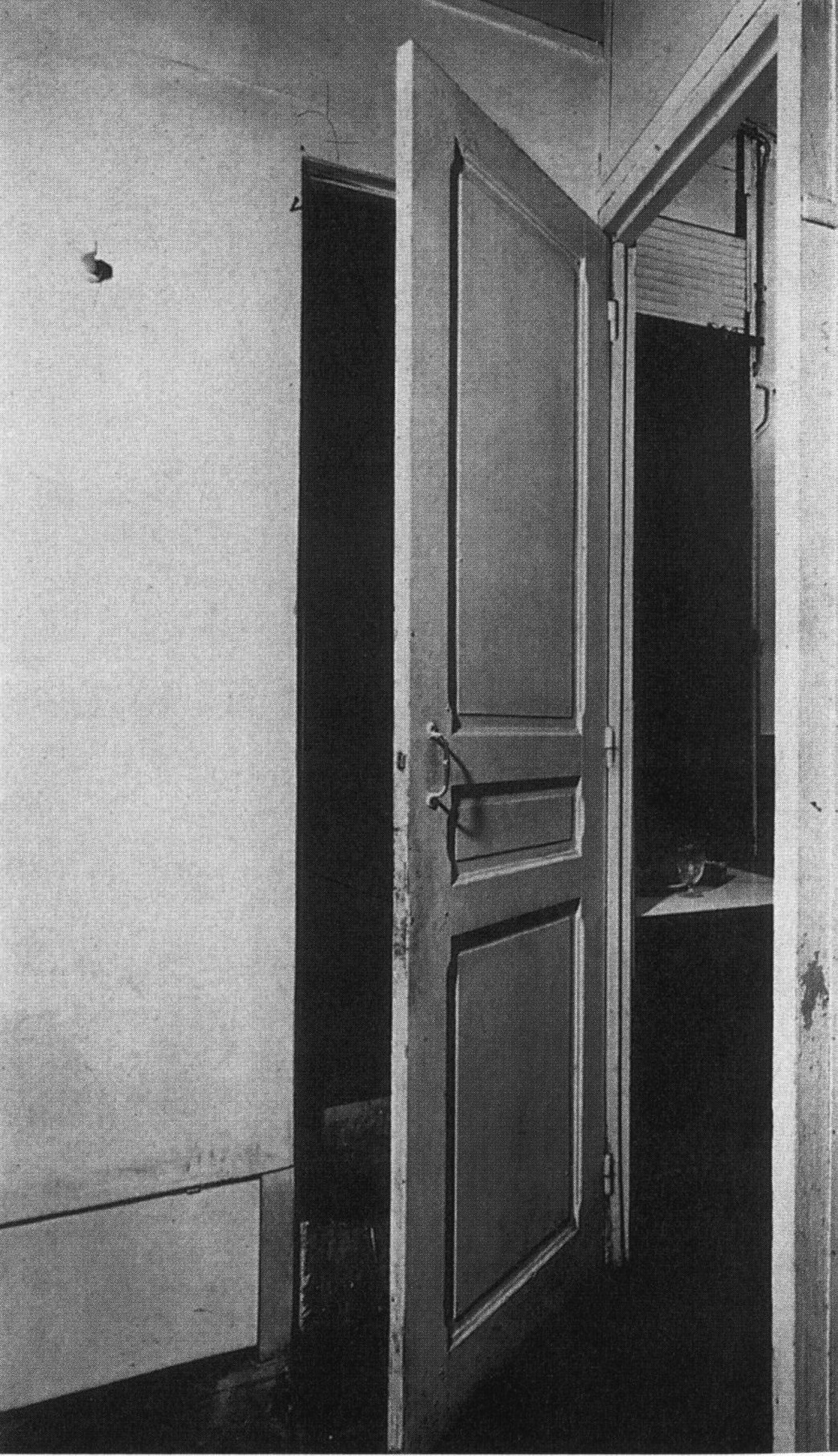

Picture taken by the São Paulo Fire Brigade after the fire at the Cinemateca Brasileira, July 2021.

This is a take on my long-lasting research/practice about the possibilities of collecting and manipulating pre-existent digital files as a source material to produce artworks.

Picture taken by the São Paulo Fire Brigade after the fire at the Cinemateca Brasileira, July 2021.

As an artist-in-learning mostly working with found audio-visual paraphernalia, that is, historical material (such as sound, photography, film, newspaper, text etc.) often dependent on preservation, following the situation of the Brazilian Cinematheque (Cinemateca Brasileira) over the last few years makes me feel somewhat impotent, helpless.

Controlled by the Federal Government, the institution stores what remains of the Brazilian film anthology, as well as cinematographic equipment and documents such as posters, scripts, newspaper articles, books, photographs – among other important stuff that materially portray a lifelong audio-visual history from a country.

Its abandonment escalated in absurd ways from 2019 onwards, being specially affected during the coronavirus pandemic. The Cinemateca had its keys taken by the responsible Secretariat and closed in August 2020. Since then, workers have no access whatsoever to perform the necessary tasks to maintain such a collection in safe conditions.

Mournfully, a fire consumed part of its archive in the end of July 2021.

Not a misfortune, though. Rather, a long-term project carried along by dirty political interests: the erasing of a people’s shared memory.

From Cinemateca Brasileira and other sources, either public or private, it is still possible to find on the Internet some digitalized fragments of lost or damaged footage.

Driven by a desire of accumulation, I’m used to spend hours on YouTube and social medias like Facebook and Instagram – selecting, gathering, arranging, saving items.

Doing basically what an archivist does.

(It’s somehow curious the afore use of the verb to save, no?)

In this sense, the meaning of “archiving” and “creating” overlap. The boundary gets blurry.

Before an artist, I would consider myself an archivist to be honest. An archivist of ordinary digital stuff.

And consciously or not, many of us are digital archivists too.

(Try this out: just open your downloads folder, or your cell phone storage, and have a look.)

Somewhere in-between these two occupations, I feel a bit like an archaeologist too. Excavating findings, I learn from the remains.

What’s “out there” shapes my craving for ideas and potential projects.

///

Dialogue from the film Terra em Transe / Entranced Earth (Glauber Rocha, 1967)

To my work, files available online are the source for a future haunted by the past. These files have a power within themselves because they represent reminiscences, breadcrumbs, ashes.

They somehow survived, so to speak.

As ghosts, they embody a sense of timelessness – a time that is past and at the same time is yet-to-come.

Once wandering around the vast and erratic Internet dimension, they are made accessible.

Now in a constant state of metamorphosis – both in substance and experience they offer.

And for being accessible, mere archivists like us become traders of those findings, reclaiming them to a broader collective use.

Dragged into their active sharing, we are allowed to edit them, convert, reformat and fragment them; (mis-)translate them.

Cannibalist Manifesto

(Oswald de Andrade, 1928)

The Cannibalist Manifesto (Manifesto Antropófago) was published in 1928 by the Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade. According to his innovative writing and ideas, it was precisely the cannibalistic/anthropophagic roots of Brazil what has allowed its people to critically comprehend, in the cultural field, European and other foreign models.

Brazilians, then, should be proficient on ingesting forms-styles-patterns imported from abroad to produce an art that would be genuinely national (and not simply a copy).

I use this metaphor of anthropophagy, however, on behalf of my own artistic practice.

Living in the era of over-documentation induced by social medias, I endorse a solid position to the web’s ecosystem – of not generating any new images but instead recycling already existing ones.

Every copy manifests originality – even if the originality itself lies in the very act of copying.

Thus, I understand copy as a creative gesture; almost an organic, natural flowing process.

Grabbing excerpts from a given context to further rearrange its architecture and surroundings.

To create conflicts (with)in the material.

Think of a reframed image as a plastic surgical procedure: though it continues to be that same image, or a detail of it, it is now transmuted into something else.

As Duchamp’s found, ready-made objects (objet trouvé). Or Plunderphonics’ recordings. Yet they are their own source, they also are something completely new, unique.

Marcel Duchamp's Door, 11 rue Larrey (1927).

A constant theme to my projects is the (micro-)universe of football. To beyond the game itself, football is a paradoxical territory of conflict where political issues extrapolate the stadium.

Motivated by the COVID-19 pandemic situation, which changed the essence of football by extracting what is most valuable in it – the fans, their energy and devotion – FEVER PITCH is a multi-channel sound installation that reflects on the roles of sounding and making sounds in the embodied experience of the play.

It consists of four short-range FM transmitters (each one performing an audio channel) and 12 second-hand pocket-radios attached to the wall, resembling a football team line-up. The listeners may also approximate their ears closer to the radios if they want to listen to specific sounds coming from distinct sources.

All the chants in the installation are sung by fanbases of different South American football clubs and follow an idea of motivation, passion and death as a basis to explore narratives of affection, belonging, and also a critique to the position of football – which, despite facing a pandemic, continued non-stop.

///

Estadio Nacional (Santiago, Chile).

Most of the files composing FEVER PITCH have been gathered first as videos from YouTube, and then converted into sound.

By sampling, incorporating those discarded, disembodied files into a new framework, into a completely different context than their original one, I creatively interfere with what from scratch was not (meant to be) together.

(The default and core operation of what I call creative interference is the cut – an exploratory and most of the times intuitive path where the material itself guide me through via editing/montage.)

And finally, through a praxis of bricolage, I recycle not only the content but also the medium through which the sound is reproduced.

No vengo por salir campeón,

Vengo porque te quiero.

Yo vengo para recordar

A los que ya se fueron.

Doy gracias a todos los que dejaron la vida,

Esta barra no se olvida,

Los lleva en el corazón!

///

I don’t come to be a champion,

I come because I love you.

I come to remember

Those who have passed away,

I thank all of those who have left this life,

This crowd won't forget you,

We carry you on our hearts!

“No vengo por salir campeón”

– Los Piratas Celestes de Alberdi, fanbase of Club Atlético Belgrano (Argentina).

Akira Kurosawa.

Andrade, O. (1991 [1928]). "Cannibalist Manifesto". Trans. Leslie Bary. Latin American Literary Review, vol. 19, no. 38, pp. 38-47, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20119601.

Goldsmith, K. (2020). Duchamp Is My Lawyer: The Polemics, Pragmatics, and Poetics of UbuWeb. New York: Columbia University Press.

Steyerl, H. (2009). "In Defense of the Poor Image". e-flux, no. 10, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/.